I recently returned from a trip to the US, arriving at Melbourne airport at around 6am. What greeted me was not the highly efficient, and automated customs smart gate system of my normal Melbourne experience, but general panic and confusion and very long queues.

First, let me set the scene. My initial signal that all was not well, was that the two lonely smart gate sentinels, that greet you as you turn into the duty-free area, they were not working. In fact, one of them was open, baring its soul to the outside world, almost like a car on the side of the road with its hood up, indicating to all passers-by that all was not as it should be. As I passed, I looked further down the corridor to the bulk of initial machines that greeted travellers to see if I could use one of those. To my dismay these were all showing a red screen of death.

It was then that the queue began to form. And what a queue it was. Imagine from 5-10 heavies arriving from long haul flights. Each disgorging around 250-350 tired and smelly passengers, all converging into a customs area, armed only with a skeleton crew to babysit the machines and support the non e-passport passengers. It was a perfect storm, and a great test of business continuity and disaster recovery.

I stood waiting in this mass of human confusion, watching my time dwindle away, and coming up with excuses to the kids as to why dad, after being away for a while, couldn’t meet his commitment and take them to school that morning.

Whilst enjoying the joys of the modern man-made marvel of queuing and queue theory, I thought I might as well take the opportunity to evaluate what was going on. I put my design hat on to evaluate how this situation could have been handled better. A few things dawned on me during this cognitive escapism which I thought I might share.

Human behaviour and dark matter

Humans are amazing creatures. In the absence of information and in somewhat chaotic situations, creative desperation kicks in and we begin to innovate and improvise. This is what I observed was happening.

On arrival in this mass of travellers, there was no information available. No one knew what was going on for at least the first 30 minutes. In the absence of information, people fill in the gaps. It’s the same as rumour, slander and gossip. In the face of limited communication or untrustworthy information, humans will fill in the gaps, and act upon their interpretations.

When studying human behaviour, a structure exists of five human factors that you should consider, sometimes you can layer these hierarchically. It starts with societal, then organisational, team, psychological and physical. So, let’s use this as an initial guide to understand what was occurring.

Physical: The queues were getting longer, machines were not working, there were no signs or visual/audible aids to indicate what was going on. Physical signage existed but only for the main success scenarios to guide people to the right gates.

Psychological: Each person now interprets the data, or lack of it, using their own heuristics, assumptions and insights. They feel the pressure of the masses, they are tired, nervous, worried about meetings, kids, traffic on a Monday morning etc.

Team: In creative desperation, people find solutions, and in the absence of communication and information, packs begin to form around similar interpretations of context. A few realised that if you take a shortcut through the duty-free area you can jump the queue. All it takes is one person to see this, then the organisational and societal boundaries setup around queues, highly secure areas, and the right or wrong gates to use, begin to dissolve. One or two people are enough to cause this, resulting in a pack forming. As more join, they are freed from the confines of the rules of this area and think “well, if others are doing it, I won’t get myself into trouble”, and they follow. Sheep bleating anyone?

Then the floodgates open. In a matter of seconds, the entire duty-free area is completely gridlocked with people. Like a fire that has a wind direction change, the front has just gone from 5 people to 50 in a matter of seconds. The physical gate size, that receives people into the processing channels and queue mechanism, has not changed, but the funnel has grown exponentially. So, we now have a 50 people wide queue all contending for a small slice of limited channel slots to get into the normal queuing system.

Organisational – I have made hints to this one. Organisational refers to the rule’s setup by the organisation, in this case, Melbourne Airports and border control. These rules are normally quite strict and relate to which queues you must go into for which passports, no cameras allowed, no cell phones to be used, who can shortcut, who cannot, organisational rules etc. In the absence of anyone enforcing these rules, due to lack of information and desperation, these boundaries are soon discarded. People fall away from organisational rules into team and pack mentality quit quickly. In other words, the size of the unit gets smaller, and more agile.

The new team packs are the innovators jumping away from the enforced constraints of some organisations to seek new ways to get past the blockage. The first few made it to the front, but without consideration of the damage to the entire system and everyone behind. The result, in fact, created a significant negative impact to all others, grinding the entire system, and the engine of crowd management to a halt.

Societal – at the top of this pile are the societal rules we live by. Whether its chivalry, respecting queue sequence, personal space and bumping one another or respect for authority. In the absence of information, this was the first to crumble. Regardless of whether you were man, woman, child, male or female, aircrew or passenger, it became a free for all to overcome the problem. We know, from broader society, that when the societal level begins to crumble you move down to the next level, when that crumbles you move to the next, and ultimately down to one. We see this in politics and have many historical systems to learn from e.g. the Roman empire. When the societal level (the nation) collapses, the next level down is to party level (left or right wing), when that collapses the next level down is into tribes. Smaller and smaller we go until you just look out for number one. Some of you may notice the recent polarisation occurring in our western societies around left and right wing. Perhaps for another conversation.

What was interesting was that even in this chaos, when the 50 rows hit the two channels they needed to squeeze into, they still organised themselves into the two channels. One for e-passports and one for analogue passports. Even though it was evident that none of the smart gates were working, the societal pressure to adhere to the organisational layers was still partially in place, so too was the respect for queuing. This too changed very quickly as soon as someone, who shall remain nameless, decided that the two queues did not make sense and that all gates, regardless of organisational instructions, were potential gateways to freedom. So began another pack, until a following ensued causing that channel to also fill up.

It’s worth noting that organisational and societal layers are a form of dark matter that strategic designers must consider when looking at human behaviour and complex systems. Dark matter is a term drawn from theoretical physics. It is believed to constitute 83% of the matter of the universe, yet it is virtually undetectable. It neither emits nor scatters light. It is believed to be fundamentally important in the cosmos, and yet there is essentially no direct evidence of its existence, and little understanding of its nature. The only way it is perceived is through the effect on other things. With a product or service, the user is rarely aware of the market and organisational context that produced it, yet the outcome is directly affected by it.

This dark matter can be seen as a level higher that societal layer, but for the sake of this conversation let’s keep it in the societal and organisational layers. It is a mix of culture, policy, market mechanisms, philosophies, legislation, third cultures, finance models, traditions, beliefs, habits, national identify etc that decisions are produced within. Dan Hill does a great job of introducing this in his book “Dark matter and Trojan Horses”.

The dark matter surrounding this might relate to the national pride around being an Australian when you return home, the tall poppy syndrome that affects your perceptions of people, racial, class and religious biases that you might have etc.

Anyway, you get the picture. Hopefully you can see that, when you are designing for complex systems, it pays to look for the evidence of dark matter and its influence on how things work.

Dark matter and terrorism

In considering all the behaviours I observed, I noticed something occurring off to the side of me. There were two customs officials with a piece of paper in hand looking for a known “person of interest”. I knew this because the A4 sheet was pretty thin and hence partially see through. I got a view of the Caucasian of the man and his physical appearance and did a scan around the hall to see if I could see him. As I was doing this, I was suddenly reminded of a book I had read called ‘Change by design” by Tim Brown, CEO of Ideo.

In it the IDEO team had to help the TSA (US Transport Security Administration) deal with the issue of improving the human experience through the security checkpoints. I think we can all empathise with the need to find improvements in this area. However, a shift needed to occur away from the detection of harmful objects to the detection of hostile intent. The hypothesis was that if you could reduce the stress level of everyone in the system, the person with hostile intent, and exhibiting more than average stress, would be more noticeable.

In thinking through this hypothesis, it dawned on me that the reverse might apply. If I wanted to sneak some terrorists into the country, this would be the perfect way. Bring down the technical system and up the stress level of everyone in the system, passengers and border agents primarily, thereby reducing the mental effectiveness of being able to identify possible people with hostile intent.

It also dawned on me that the environment at the time would be the perfect spot for an attack. Multiple nations all squeezing through one choke point. Mmmm, I think I had travelled a road too far now…and look, I made it to the front. Time to get home to the kids.

Conclusion

What can we, and perhaps Melbourne airport and border control, learn from this?

- Give lots of physical information early on and often. Tell people what’s going on; provide status updates shouted verbally or over the PA, as soon as possible and continually.

- Leverage the crowd. Ask for the crowd’s help and understanding. Rely upon crowd dynamics to spread the word, as well as the hidden societal and organisational expectations.

- Keep the appearance that the societal and organisational aspects are still intact and working. Understand human dynamics and design and prepare for the situation with backup signage and processes.

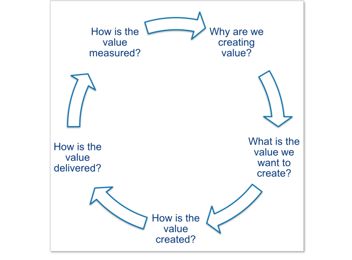

- Design for all 5 factors. Use the disciplines of CPS (creative problem solving), systems thinking, strategic design and design thinking to consider all aspects of human behaviour and how to design services around this.

- Design for the outliers. Most problems are in the dark matter space. To develop solutions for the future, we must learn how to think within, and plan, for the dark matter areas of societal, organisational and team mechanics. Technology alone does not solve complex problems or chaotic situations. To be agile in these situations, you need to have experimented with scenarios based on human behaviour, and designed services around these. In the case of the smart gates, technology introduced efficiency, but this efficiency effected the broader structures that were needed during a chaos situation. Were the other human factors considered when applying technical solutions to a complex system such as this?

That’s my thoughts on this. For some more reading in this space be sure to get your hands on the following:

- Recipes for systemic change – Bryan Boyer et al

- Change by design – Tim Brown

- Dark matter and trojan horses – Dan Hill

- The essentials of Theory U – C. Otto Scharmer

- Behavioural economics and policy design – Donal Low

- The Black Swan by Nassim Nicholas Taleb